Going Racing Used to Sell Cars. It Still Can, Provided Brands Succeed In the Consumer Translation.

In the early days of advertising, the messaging for any product-type, cars included, was very straight-forward. In the automotive industry, brands would win something hard (Le Mans, Paris–Dakar, Pikes Peak, etc) and then say it, loudly, in a single declarative line.

The ads weren’t subtle because they didn’t need to be, and the messaging boiled down to a very straightforward message consumers could latch onto: we proved ourselves under the harshest conditions on earth, so you can trust (and desire) what we sell you.

That era produced ads which are still exciting today because the logic chain was simple, culturally acceptable, and repeated often enough that the public learned the language.

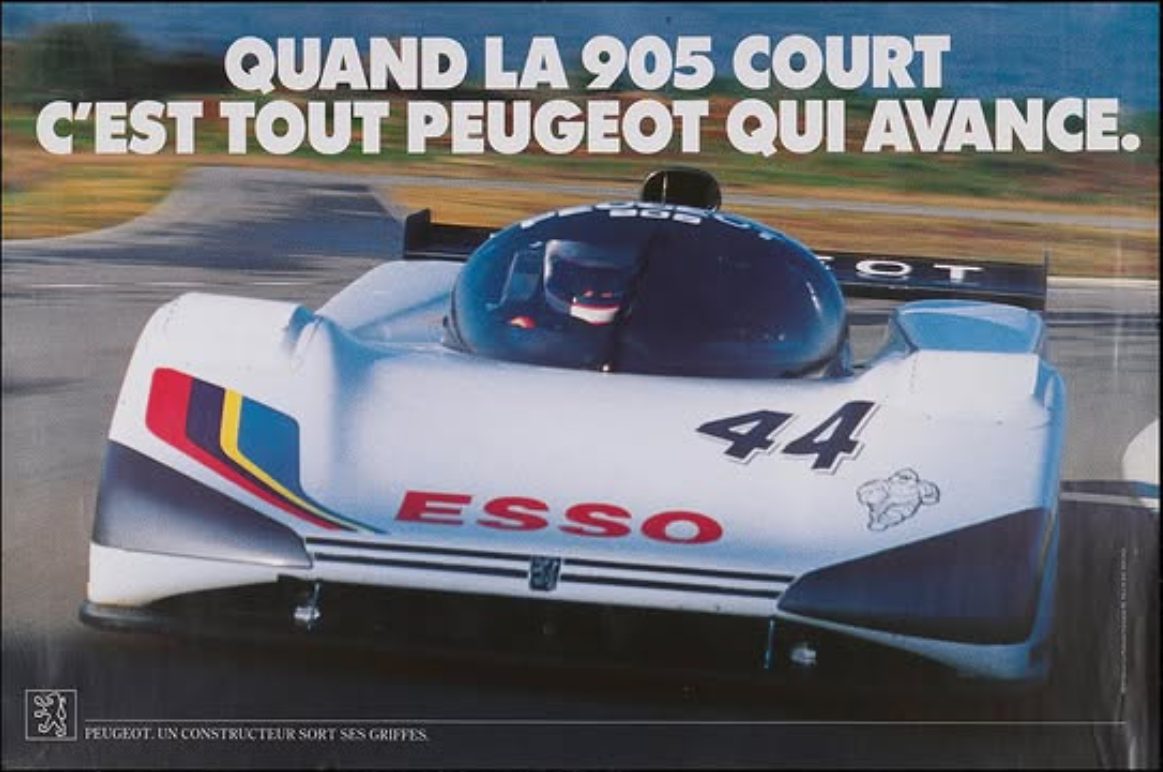

Look at the classic French poster tradition: Peugeot turning endurance results into a one-line manifesto, Renault and Alpine compressing a race result into a claim about efficiency, durability, and engineering pride.

The ads leveraged heritage to build a commercial bridge between competition and commerce; motorsport was not a corporate vanity project, it really was a selling tool.

Today, that bridge has not disappeared, but due to the changes in the advertising and consumer spaces, it has nevertheless been weakened, fragmented, and increasingly under-monetized.

To be clear, if you scroll the main Instagram accounts of major car brands (not their dedicated race-team accounts, which we can hypothesize are less likely to be followed by casual car buyers who do not follow motorsport), you will still find racing content: podium shots, livery glamour, race-week hype, driver quotes, heritage throwbacks.

However, that does not contradict the argument; in fact, it proves it.

Racing has not vanished from communications, but what has receded is the disciplined translation of racing into repeatable, consumer-converting arguments at scale.

In other words: brands still feature racing, but they don’t fully monetize it.

Racing appears in content; it disappears in conversion.

Don’t want to be left behind?

Subscribe to Return On Racing — the weekly newsletter from Vaucher Analytics covering actionable motorsports strategy, cost breakdowns, and sponsor intel.

Connecting the Race Track to the Showroom Is Now an Existential Challenge

Due to factors outside the scope of this article, Chinese EV makers are structurally set up to win in a paradigm where a car is simply an appliance meant to transport people: faster iteration, aggressive pricing, and feature density that legacy brands struggle to match at scale.

If the buying decision collapses into specs relative to monthly payment, legacy brands are fighting on the one dimension where they’re least advantaged, and that becomes existential, very fast.

That’s why going racing matters, full stop, but the rewards of those investment then need be fully realized through customer outreach and communication; many automotive brands are not currently following through.

Motorsport is one of the few defensible “emotion factories” left: it creates meaning, desire, and willingness to pay when products converge. Crucially, motorsport moments are genuine, and genuinely awesome, meaning they are placed well-above the AI generated content that is already being used heavily in marketing circles.

The problem is that automotive brands increasingly treat racing as punctual race-week content instead of translating it into repeatable consumer-facing reasons to buy.

At the most basic level, this is marketing and unfortunately, marketing is one of the first line items on the chopping block when an industry’s fortunes change; exactly where the legacy automotive industry finds itself now in the face of tariffs and competition from Chinese EVs.

Scaling back the links between the track and the showroom, or even pulling out from the race track entirely, would be understandable in the short-term, but would be especially catastrophic at this historic turning point in the world’s automotive market.

Vintage Peugeot ad with the tagline “When the 905 races, all of Peugeot moves forward” (Image source: Instagram @archivesautomobiles)

The Modern Paradox: Racing Is Bigger, But Racing-Based Selling Is Smaller

In many markets, motorsport has never been more visible.

Formula 1 is mainstream entertainment.

Endurance racing is resurgent.

Social platforms amplify highlights and personalities.

And yet, if you watch most mass-market automotive advertising, you’ll see very little direct leverage of racing heritage or racing performance as a structured reason to buy; certainly not to the extent of the Peugeot example above.

You’ll see lifestyle associations, safety ratings, financing options, tech features, comfort packages, and a carefully sanitized version of mobility, but racing and motorsport?

A race car, if you can find one at all, is often confined to a corner of a brand’s website.

That’s a strategic failure.

If your automotive brand is spending meaningful money on racing but not converting that expenditure into consumer belief and preference, your money is going no further than your suppliers’ pockets.

Motorsport can still sell cars, but only if you treat racing as an input to a marketing system, not an isolated communications moment at worst, and an R&D test bed at best.

Why Car Brands Rarely Translate Racing Into Sales Today

The reality of large organizations in 2025 is that modern automotive marketing is run inside a web of constraints that didn’t exist when many classic car and posters were made.

Some of those constraints are external, but many are self-inflicted.

First, the volume reality changed

A significant portion of today’s sales are crossovers, leases, fleet deals, and financing-driven transactions. The buyer in these scenarios not looking for a performance identity, they’re looking for low risk and low friction.

Marketers respond to that by pushing “safe” value propositions: monthly payment, convenience, tech, and warranty terms.

Racing feels like something that excites enthusiasts, and many brand teams assume enthusiasts don’t drive volume.

Second, legal and brand safety pressures tightened the leash

In a world more sensitive to road safety and reputational risk, many brands avoid anything that could be interpreted as encouraging speed; a line that used to read as swagger can now read as irresponsibility in an internal review.

The result is an overcorrection: brands strip out performance messaging entirely instead of learning how to communicate racing without implying reckless driving.

Third, the product link became harder to explain

Motorsport used to be visibly related to road cars: homologation specials, recognizable silhouettes, tangible mechanical overlap, and enthusiast culture. Brands went to great lengths to make this case, one such example being the WRC Group B Peugeot 205 T16.

Vintage ad for Michelin tires showcasing their use in rallying on the Peugeot 205 T16. Caption: “I score points and drive on Michelin tires”. (Source: eBay @RallyPassions)

The 205 T16 had essentially nothing in common technically with the road going Peugeot 205 introduced at the time, but the former was made to look like the latter, which helped sell so many 205s that it literally brought Peugeot back from the brink.

Today, the “thing you race” and the “thing you sell” often share less obvious DNA, but even when your best-selling product is a heavy hybrid or EV crossover, the traditional “we’re fast” claim isn’t the right bridge, that doesn’t mean no bridge exists.

It means marketers have to build a new one, and many don’t know how, leading to massive lost opportunities.

After all, if your brand is involved in motorsport nominally “just” for R&D (a very traditional internal justification for keeping a motorsport program going) , if that R&D does trickle down to the consumer segment, why not tell consumers about it?

Fourth, channel fragmentation overturned old marketing practices

Vintage ads were designed for print, billboards, and TV environments where the viewer gave you time because they didn’t have many choices.

Today you get a couple seconds, on a small screen, with dozens of other apps running in the background. If your racing connection requires a lot of explanation, it can’t survive modern attention spans.

Brands know this, so they default to generic lifestyle imagery that “works” in the most shallow performance-marketing sense, because it reflects the same shallowness that makes up the average social media feed.

Fifth, performance marketing warped creative incentives

If your internal scorecard is dominated by click-through rates, short-term conversion, and attribution models that can’t capture brand preference shifts, motorsport becomes hard to justify. Racing tends to operate as a long-cycle brand asset, the exact kind of lever that gets deprioritized when teams are judged on immediate numbers.

Sixth, org designs are not adapted to the task

This is the part nobody wants to say out loud, but organization designs are broken.

Motorsport sits in one silo, brand marketing in another, regional sales in another, and retail execution in another.

Consequently, budgets, approvals, and KPIs don’t align, so the easiest path becomes a low-effort race-week post and a hospitality program, while the expensive part, converting motorsport into mass-market belief, never becomes any one person’s job.

The result is predictable: racing content on main brand accounts falls into four safe buckets: event coverage, brand-world aesthetics, partner obligations, and the occasional hero film.

None of those are inherently bad. But most of them don’t answer the buyer’s question: “So what does this do for me and the car I’m about to buy?”

That gap, between racing presence and racing persuasion, is where the ROI leaks out.

The Fix: Make It So the Race Never Stops At the Chequered Flag

The opportunity isn’t to go back to old posters exactly as they were.

The opportunity is to preserve what made them work: clarity, confidence, and repeatability.

Once the message is set, update the “why it matters to me” translation for today’s buyer.

How then to determine that message?

Every brand is different, so it’s important to start with a matrixed model that associates actual racing and performance know-how (“proof”) with an established racing heritage that allows audiences to believe this technology makes a manufacturer a performance brand (“halo”).

More specifically, the proof and halo axes are defined as follows:

Proof: In this framework, “proof” is motorsport-derived proof, that is to say hard transfer or soft validation you can translate into a defensible consumer claim, not generic engineering competence or impressive specs.

Halo: “Halo” is brand permission/mythology, that is to say whether the audience accepts motorsport as a credibility-and-desirability amplifier for the brand, this must be earned through consistent products and positioning.

Since every brand will have different levels of proof and halo, the marketing and communications systems will vary according to where a brand falls in the matrix.

Furthermore, brand permission is geography-dependent. The same OEM can be “earned performance credibility” in one market and “rental-spec appliance brand” in another, which means the exact quadrant can shift by region.

The illustrative examples below are framed primarily through a European lens, where heritage, premium signaling, and motorsport literacy are generally stronger, but where compliance pressures can also shape what brands feel comfortable claiming.

Quadrant 1: Hard Transfer + Halo (High Proof / High Permission) — Example: Ferrari

This is the ideal state: the motorsport program has clear, believable product linkage and the brand has earned the right to lead with emotion.

In Europe, Ferrari is the cleanest “win → desire → pricing power” machine: the product experience, the racing story, and the cultural myth all reinforce each other.

The audience doesn’t require a long technical explanation because the brand’s identity already carries permission; the racing result functions as evidence, not argument.

In this quadrant, the creative can be unapologetically declarative: racing isn’t decoration, it’s a commercially potent proof of why the brand deserves its margin. Incidentally, Ferrari has transcended even this stage: it has no traditional marketing spend to speak of, going racing is the marketing.

Quadrant 2: Proof-Led Translation (High Proof / Low Permission) — Example: Toyota (main brand; with GR nuance)

Here the product linkage is real, but the brand lacks permission to lead with pure emotion at mass scale.

In Europe, Toyota is respected for engineering competence and reliability, and it has genuine motorsport receipts, but the mainstream brand’s permission is still “smart, rational choice” more than “mythic performance icon.”

That’s why the right play is proof-led translation: use racing as a validation environment and convert it into consumer-relevant claims that feel responsible and credible (durability, efficiency under load, system integration), rather than “we’re fast.”

A key nuance: Toyota GR can approach Quadrant 1 in enthusiast contexts, but the Toyota masterbrand typically sits in Quadrant 2 when speaking to the broad market. CEO Akio Toyoda went on record years ago saying the company would no longer make “boring” cars and it appears anecdotally that this starting to alter perceptions in enthusiast circles; time will tell how this perception carries over to the broader consumer market.

Quadrant 3: Halo-First Racing (Low Proof / High Permission) — Example: Bentley

In this quadrant, direct product transfer is weak or hard to explain, but the brand has strong permission to use racing as identity.

In Europe, Bentley can credibly trade on glamour, heritage, and association; motorsport functions as a meaning engine, reinforcing aspiration and cultural relevance even when the buyer can’t point to a specific piece of tech that migrated from track to road.

This can still sell cars because desire isn’t rational; it’s justified rationally after the fact. However, this is fragile: halo must be anchored by at least one credible “spine” (design coherence, consistent brand behavior, a clear brand truth) or it starts to read as expensive theater.

Quadrant 4: Racing as Content, Not a Sales Lever (Low Proof / Low Permission) — Example: Genesis (and why Hyundai N is different)

This is the danger zone: weak product linkage and weak brand permission.

In Europe, Genesis is still building broad cultural permission, which makes heavy motorsport-led consumer selling risky: if you try to run “racing proves we’re desirable” too aggressively, you can trigger the “cool race car, shame about the brand” reflex.

That doesn’t mean racing is useless; it means the objective should be narrower and more strategic (credibility building, partner value, employer branding, or targeted enthusiast/community activation), while the consumer-facing story stays grounded in claims the brand can already own.

A crucial clarification: Hyundai N is not Quadrant 4. Hyundai’s N sub-brand is closer to Quadrant 2 (real proof, still earning permission outside enthusiasts), which is exactly why separating sub-brand permission from masterbrand permission matters in this model.

The Modern Playbook: How to Use Racing to Sell Cars in 2026

To make racing an actual sales lever today, you need a system, not a campaign.

Start with the translation question before you shoot a single ad: what does your racing program prove that a buyer can understand in one sentence?

Can a salesperson in one of your dealerships convey this in less than 5 seconds?

If you can’t answer these questions crisply, you’re not ready to advertise motorsport; you’re ready to post about it; a great, performance-related example from the past is Dodge’s “Does That Thing Got a Hemi” message.

With that in place, build a messaging ladder that moves from result to relevance; the mistake brands make is they stop at “we raced” or “we won.”

Winning is not the consumer benefit, winning is the evidence.

The consumer benefit is what the win proves about the product or the brand.

Next, choose your tier on purpose.

If you have hard transfer, lead with it. If you don’t, lead with soft transfer and earn the right to halo.

And if you do lead with halo, anchor it with a foundation, one tangible proof point, one engineering truth, one reason the consumer shouldn’t roll their eyes (another great example from the past is how the original Honda/Acura NSX ended up with Honda’s VTEC technology despite originally including it).

Finally, industrialize this system across channels.

The old marketing paradigm produced iconic posters because a single idea could live for months in mass media.

Today you need modular assets that repeat the same proof in different formats: short cutdowns that hook in seconds, declarative-style executions that build fame, a landing page that explains the translation for those who care, and retail/dealer materials so the story doesn’t die at the point of sale.

This is the adage “marketing is about telling one thing a thousand times, not a thousand things one time”, and if your motorsport story can’t be explained by a salesperson in one breath, you’ve built brand content, not a sales tool.

A simple litmus test helps separate “racing content” from “selling with racing.”

If a post, film, or campaign does not do at least one of the following, then it is not monetizing motorsport, but just appearing in your brand’s feed: make a clear product-relevant claim, provide evidence, draw a bridge to a buyer benefit, give a next step.

What Most Brands Still Miss: Motorsport Isn’t the Advantage. Systematic Messaging Is.

The real competitive edge isn’t simply showing up to race.

It’s a great time to be a race fan, with plenty of brands going racing in this motorsport golden age.

The edge is being the brand that can clearly answer: so what?

Customers don’t have to think about what you proved, what you learned, what it means for them and for you, and why they should care.

This matters more now because the auto market is entering an era of collapsing functional differentiation. EVs, software-defined vehicles, and globalized supply chains are compressing product gaps.

When features converge, meaning becomes the battlefield, and going racing is one of the few remaining factories of meaning in the car industry, but only if you convert it into consumer belief.

If you’re not racing, you’re letting others manufacture desire while you compete on incentives and spec sheets.

If you’re racing and not selling with it, you’re leaving value on the table.

Either way, the conclusion is the same: going racing can still sell cars, but the era of lazy motorsport marketing is over.

Brands that want the upside will have to earn it.

Are You Positive Your Brand Is Capturing All the Value From Its Motorsport Program?

Vaucher Analytics helps automotive leaders evaluate how regulation, brand equity, and motorsport strategy interact, before capital is irreversibly committed.

If you are responsible for long-term product, brand, or regulatory strategy and want to pressure-test assumptions, you can reach me at contact@vaucheranalytics.com

Main image source credit: www.gridfiti.com

Social media image source credit: Instagram @archivesautomobiles